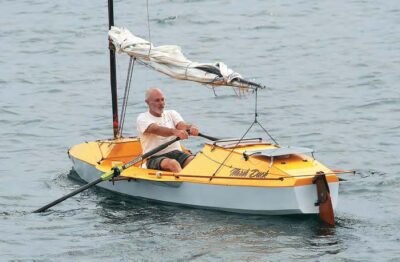

The Laughing Gull is a 15′ 9″ gunter-rigged sharpie sloop designed by Arch Davis. Early sharpies were used by oystermen in Long Island Sound in the latter part of the 1800s for sailing shallow waters, including skimming over sandbar shoals to get their hauls quickly to market. They had flat bottoms, single hard chines, and very shallow draft. Ralph Munroe, yacht designer and jack-of-all-trades in Coconut Grove, Florida, further refined the design in the late 19th and early 20th century. His most notable design was a 28-footer, EGRET.I began building my Laughing Gull in the summer after my junior year in college. I had admired Arch Davis’s designs since middle school, and called him about building a boat. He sized up my interests and skill level—only birdhouses and bookshelves at that point—and recommended the Laughing Gull. He had designed the boat with young people like me in mind. It would be simple to build, thrilling for a youthful crew hiked out on the rail as the skiff leapt up on a plane downwind, and forgiving when capsized.I soon had the 110-page building manual and plans in hand. Shortly thereafter, my shipment of marine plywood arrived. Mr. Davis generously made himself available for free phone consultation, but his written instructions were so thorough, I hardly needed to call. Only basic carpentry tools were required. I did not own a tablesaw, so I borrowed one from friends. The only things I did not make myself on the boat were the sails and hardware.

Join The Conversation

We welcome your comments about this article. To include a photo with your remarks, click Choose File below the Comment box.

Hi. I am Peter’s mother. This is a great article and I can attest to the fact that the CAROLINA ROSEO has been a joy in Peter’s life. I have to say that I feel vindicated by Mr. Davis’ comments regarding how the boat should be used and in what conditions. Hearing of Peter’s adventures has been stressful at times!

Peter has had only the best things to say about Mr. Davis and his continuing guidance.

Beautiful boat, Peter. Great article.

Thanks, Bill! much appreciated.

A detailed and engaging article on the joys of building a skiff and then sailing the hell out of it. I should just say, you don’t have to be young to get a kick out of sailing hard and fast. I have just finished building a Goat Island Skiff and am looking forward to scaring myself silly in the coming weeks. I am 74.

That is great to hear, Harvey. Did not mean to exclude at all!

Hope we can see your story on these pages soon.

Thank you for your kind comments.

Over here in the UK, I run a small sailmakers ( R.& J. Sails) where we specialise in sails for small boats. Consequently we make a number of gunter mainsails, and I would agree with a customer who commented that the gunter main is quite a difficult sail to make. Although, looking at your sail, I would comment that your sail has been correctly made. The problem with a gunter mainsail is judging how much the gaff will “drop back” from the mast, especially as there are a number of different methods and knots used for attaching the halyard. As a generaliZation, I would say that it is better to allow for too much drop-back than not enough, as if it is too little, it will develop a crease radiating from the throat down to the clew, and you comment on this in your article. It is something dinghy sailors would refer to as a “luff starvation crease.”

Regarding the problem encountered with the gaff jaws, this is a common problem and here are some notes that I hope you and your readers will find helpful.

1. The position of the gaff halyard is critical, the ideal position is 50% of the length of the gaff, however many rigs function satisfactorily with a 40% distance between the throat and the head positions. Looking at the photos, I would calculate that yours is only about 33% If the headroom under the boom can be reduced, try moving the halyard attachment up as far as possible towards the 50% mark. If this is not possible the only solution would be to make a longer gaff and have the sail modified to the new length.

2. You comment that “you should stretch the sail tightly along the gaff” In my experience this will not achieve anything other than permanently stretching the sailcloth along the head of the sail, however there is a proviso in that it depends if the luff rope has been put in tight or even shrunk, which means undue force will have to be applied to this side of the sail. Again the photo appears to show that you have judged it correctly, but if it has been put in tight or shrunk it is easily corrected by your sailmaker.

3. However, we have found that the tape and rope along the luff should be put in tight, sufficiently so that a 2:1 or 3:1 downhaul should be used to pull it out to its correct length. Looking at the “yoke gooseneck,” you could rig a handy billy between the bottom of the boom and the foot of the mast. Increasing the tension along the luff helps to keep the gaff jaws in alignment. This is modification to the luff rope can be easily completed by your sailmaker.

4. Looking at the gaff jaws, rather than tying the halyard to the gaff jaws, where it could pull to one side, I would recommend that the halyard is fastened centrally. Either to a ring bolt or even a hole though the jaws so that the halyard can be tied off with a stopper knot.

I hope that the above is helpful, and best wishes from the UK for your excellent magazine,

Dick Hannaford