In 1953, German-born Hannes Lindemann had just begun practicing medicine in Liberia and had in mind to settle into a comfortable life as a doctor when he met Alain Bombard, a Frenchman and fellow physician, who had taken an interest in survival at sea. In the fall of the previous year, October 19 to December 23, Bombard sailed a 15′ Zodiac inflatable 2,700 miles from the Canary Islands to Barbados. Hoping to address issues that led to the poor survival rates of sailors who took to lifeboats during World War II, he intended to survive by living off what the sea provided and took few provisions. He had a net to gather plankton for food, and for drinking, he had a press for extracting water from the flesh of fish; he’d mix it with seawater to extend it. Lindemann, doubting some of the claims made by Bombard following his voyage, “decided to use my own body to experience the problems of the shipwrecked; problems of nourishment, keeping the body healthy, avoiding the dangers of the sea, and, ultimately, keeping the mind healthy.”Lindemann’s first crossing of the Atlantic, made in 1955 in a 25′ dugout canoe, took 65 days, and while he had worked out solutions to many of the physical challenges, he had not solved the mental difficulties. “I had been in dire despair several times during the crossing. I had been on the verge of giving up, especially when I lost my rudder and the two sea-anchors. Consequently, I set out to prove that one can and must prepare mentally if one is to succeed in any extraordinary feat.”The preparation for his experiment in survival included what he called Psycho-Hygiene Training to “anchor auto-suggestions deep in the subconscious so that they would automatically come to assist in difficult situations.” For six months he did mental exercises, reciting to himself: I’ll make it, Keep going west, and Never give up. “Thus, my subconscious was prepared to withstand all enticements of a more comfortable life.”

Join The Conversation

We welcome your comments about this article. To include a photo with your remarks, click Choose File below the Comment box.

What a legend!

So many people seem stressed over the effects of the pandemic. They could learn a thing or two from this guy. Life IS about survival. And we are equipped with all we need to do just that.

Thanks for this, Chris.

I have a copy of The Alain Bombard Story on my bookshelf and I read Lindemann’s book decades ago but do not currently have a copy. I will definitely have to find one and re-read it.

I can relate to the idea that learning to embrace being alone on a voyage is a challenge for most of us who are social creatures. It was one of the more difficult things for me to come to grips with when I started my solo kayaking and sailing life more than 25 years ago.

Enjoyed the article on Lindemann. I really just don’t understand how anyone might decide one day: “Hmmm, I wonder…”

Most small-boat folk have somewhere in memory some version of Coleridge’s “Ancient Mariner” line: “Alone, alone, all all alone, Alone on a wide wide sea,” but that seems to be taking it a bit far.

I have in my garage, a Klepper Aerius that my grandfather bought in the late ’60s, I believe. I haven’t put it together since I took it from my Mom’s garage 4 years ago, and I doubt it has been together since the ’80s. My Dad and I once sailed it north from our cabin in Port Ludlow on a nice following wind; as we got a bit north of Tala Point we decided that discretion dictated a return, and discovered that we best, and barely, made headway back by trading turns at the oars. I don’t think we were ever in any real danger, but it did take all of what we brought to bear on the situation to feel we had stayed just this side of trouble. A bonding experience

I really don’t mean to dismiss the amazing and heroic accomplishments of this man, but anyone contemplating the value of his experience as a lesson in how to thrive should consider that optimists who die at sea in kayaks don’t write books or give interviews.

Your point is well taken. Optimism without preparation is naïvité. It is important to keep in mind the purpose of Lindemann’s two Atlantic crossings, which was to apply some science to the problems faced by those who were forced to fend for themselves after being set adrift from sinking ships. In the conclusion of the 1993 edition of his book, Alone at Sea, Lindemann writes: “The greatest threats to the safety of a small boat lie within the person himself. Usually, a shipwreck victim will first give up mentally, then his muscles will follow. His boat will survive the longest. With a minimum of equipment and a maximum of confidence, victims of shipwrecks are far more likely to survive than perish.” That focus on the psychology of survival and a positive mental attitude is now commonplace in survival literature. If Lindemann had intended to include any advice to boaters in general, I’m sure it would have been to do everything possible to avoid being in a situation where your survival is at stake.

Christopher,

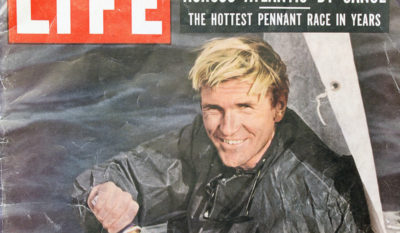

This posting brings back so many memories. My family saw the article in Life magazine and bought an Aerius that summer. I had that kayak until 1985 when I passed it on to a cousin. It started me in kayaking an̈d far too many years later, I am still at it.

Thank you for this wonderful article.

Thank you for posting this. I have Lindemann’s book Alone at Sea and read it many years ago. I also have a Klepper AE2 I bought new with a used S4 sailkit in 1993 so have a very good idea of the spatial limitations he was dealing with, although I haven’t a clue of the privations he suffered during both Atlantic crossings.

Also appreciate your insights into his calming nature; need to look into his publications on that as I think there’s something for me to learn there.

Chris,

Once again you provide an enlightening article beyond the supposed limits of a “boating” magazine. It is optimism that may make sailors chose small boats – what seems small is really much more as I am sure most of your readers would agree. Keep it up.

Excellent read about an extremely interesting and brave man. Thanks!

Read Sir Francis Chichester and his Atlantic crossings back in the ’60s in very small boat. Have lived in remote Alaska in small cabins and know of many Northern Trappers who have spent long winters. I don’t think the two extremes are not that different. You’re alone in the cabin, not moving much and scant supplies. Many have died doing this and the mental “cabin fever” did many of them in. Living on rabbits that do not have much body fat was called “rabbit starvation.”