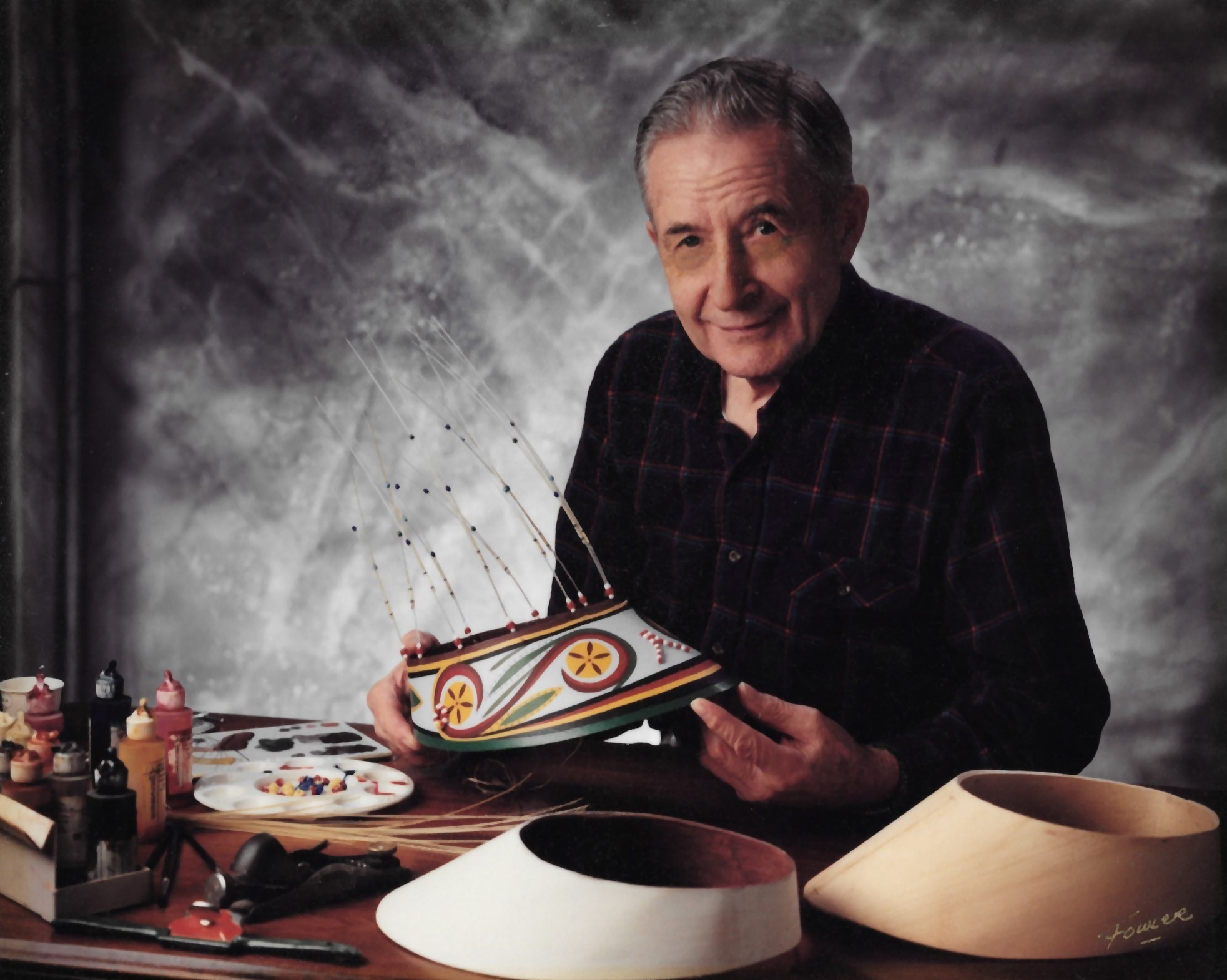

I began building reproductions of traditional Inuit kayaks in 1978 after the first kayak I’d built—to my own design—taught me how little I knew about kayaks. The Hooper Bay was the first of the reproductions I built to explore the technology of Arctic cultures whose survival depended upon kayaks; it was followed by several Greenland-style kayaks. The most sophisticated of the designs I built to was an Aleut baidarka collected in 1936 and housed in the Lowie Museum of Anthropology (now the Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology) in Berkeley, California. I visited the museum and was given access to the collection storage area to see the unskinned frame. It was beautifully carved, and each piece of wood was finely textured with the marks of the edge tools that had produced it. The baidarka was undoubtedly the work of a highly skilled craftsman and I was sure there was much I could learn by reproducing it.My baidarka clearly showed that the Lowie specimen had been very fast and had remarkable seakeeping abilities. It sparked my curiosity about Aleut kayaking equipment; I next made an Aleut paddle and bilge pump. I was also intrigued by the bentwood visors the Aleut hunters wore. Called chagudax̂, they were beautifully painted and often decorated with long, arching, walrus whiskers. To keep the whiskers from interfering with throwing a harpoon, they were usually set on only one side of the chagudax̂. The visors not only shielded a hunter’s face from sun and rain, they also put his eyes in shadow to conceal them from skittish prey. And by some accounts, the underside of the chagudax̂ made distant sounds more audible. Andrew sat with some of his work for formal portraits that were used years later for a posthumously published book, Chagudax̂: A Small Window Into the Life of An Aleut Bentwood Hat Carver. It was co-edited by his daughter, Sharon, and published in 2012. © Fowler Portraits

© Fowler Portraits

Join The Conversation

We welcome your comments about this article. To include a photo with your remarks, click Choose File below the Comment box.

When my wife saw the pictures she told me some of her 4th grade students made replicas for living history class trips to Fort Ross on the Sonoma County CA coast. (The fort was founded by Russians who brought Aleut otter hunters down the west coast hunting for the fur trade with China.)

How does one pronounce Chagudax̂ and qayaatx̂ux̂?

I’d like to try making one. Or more. Could you take a picture of your pattern with something to show scale?

I’ve had limited experience with steam (and boiling water) bending wood. My impression is that, at least for hardwood, kiln-dried is less suitable than air-dried (sometimes completely unsuitable), so I’m wondering which woods are best and is kiln-dried OK?

At the end of the article I’ve added photos that you can use to make patterns.

I have no idea how the two Unagnan words are pronounced. There is an Aleut dictionary online with a guide to pronunciation, but I wasn’t able to figure it out. The Smithsonian Institution produced a nine-part series of videos on making chagudax̂, featuring two of Andrew’s students. Several people appearing in the videos have clothing printed with the word chagudux, but I didn’t hear the word spoken. On one web site, one of the people in the videos gave the Unangan word for sea otter as chagudax (with the plain “x”) and wrote that it was pronounced “chaa-kuu-the.” The Aleut dictionary had different words for sea otter, but I think it points out that the words aren’t pronounced as they appear to English speakers.

Andrew and the makers in the video mentioned above used Alaskan yellow cedar for making the hats and visors. I used Port Orford cedar for mine. Kiln drying tends to make woods brittle and less suitable for bending, but if it is all you have, soak the shaped pieces in water for a couple of days.

Thanks so much. The pattern’s a leg up on getting started. I figure I can make a pattern out of chipboard, try it out for fit and use that to make a form. Thanks again.

Here’s a link I found for Aleut pronunciation:

http://www.native-languages.org/aleut_guide.htm

Sort of to stray from the traditional approach, I wonder if cedar strip/bead and cove might be an option. Another option might be 1/8″ veneer plywood hollow-core door skins. I love the visor worn as part of a parka hood during foul weather.

The end of the article quote: “You are a true Unangan! Our people made do with the materials available to them, right?” Scrap used hollow core doors are available in my neck of the woods – making do with materials available to me…make me sort of a mid-American Unangan, too.

A great article, Chris.